Build simple fuzzerpart 4 |

Date | |

|---|---|---|

| Category | Fuzzing |

The right way to start this part is by apologizing to all of you who waited so long for it. I had a pretty busy and yet not terribly productive week. Result was a grave need for rest and reset - that caused a delay in writing this blog post. Thank you all for the patience and I hope you will enjoy the fourth part of Build your own fuzzer series.

In the previous part we’ve added some instrumentation that allowed us to track the execution coverage. This cost us a lot of performance but it was a necessary sacrifice as the coverage is an essential part of the next iteration of our fuzzer. In the end we want it to be able to select most promising samples for further mutation and discard ones that we considered inferior. So, in essence, “it’s evolution, baby”.

As always, I will be presenting relevant code fragments but for the sake of space conservation some boring parts will be skipped. Full code, if you are inclined to read it is available at my github. Eventually commits will be tagged properly and links will point to a version of fuzzer relevant for a given part of the series.

Before we dive into genetic algorithms there are few things we need to fix and reimplement. First one is our basic coverage and how it is represented.

As you might remember we had a fairly naive implementation where we stored the address of every visited function as the binary was being executed. Only after trying to normalize and use gathered data I’ve realized I don’t need that much information. While there is a difference whether we’ve entered function f3 from f1 or f2 I’ve opted for a simpler solution. For our simple fuzzer it would be enough to know if a given function was visited at least once. To accommodate that we no longer keep trace in a list but we use set instead.

Another change is that once a breakpoint at the start of the function is hit we remove it. Like this:

def execute_fuzz(dbg, data, bpmap):

trace = set()

[...]

elif event.signum == signal.SIGTRAP:

ip = proc.getInstrPointer()

br = proc.findBreakpoint(ip-1).desinstall()

proc.setInstrPointer(ip-1) # Rewind back to the correct code

trace.add(ip - base - 1)

Astute readers will most likely notice an additional change. This change is the effect of two hours of bug hunting. It is an interesting story so please excuse the interruption and we will come back to fuzzer in a moment.

To understand the nature of the bug we need to cover a little bit of breakpoints theory. Modern computer architectures implement breakpoints either via software or hardware means. We are not using hardware breakpoints here so let’s focus on software ones. On the x86/x64 platform a common way to insert a breakpoint is to replace the first opcode of the instruction at a given address with 0xCC. That instruction, when executed, will emit a SIGTRAP signal informing the debugger to pause execution. Now, continuing program execution from here is more complicated, as we’ve just modified the code. Debugger is expected to rewind the instruction pointer by one byte, re-insert the saved opcode of an original instruction, execute the instruction and re-insert the breakpoint back. I’ve assumed that python-ptrace library is doing it for me. It didn’t.

At some point I’ve increased the coverage granularity from functions to basic blocks. And then I’ve started getting segmentation faults. Not the good ones I wanted. The bad ones, every run, always in the same place. Imagine having to debug the debugger you are currently running as well as the program you are running under the very same debugger. Fortunately, after some hours of dumping random chunks of memory and reading the code of the library I’ve realized my mistake. Solution was just to rewind the instruction pointer by one byte after removing the breakpoint.

The most surprising fact was that the previous version also was flawed. The only reason it worked was that every function had some garbage code - nop edx, edi at the beginning. Removing the first opcode just changed it to nop edx and did not influence the run of the program whatsoever.

Back to our coverage. Removing the breakpoints after the first hit resulted in a very nice performance gain. Before deciding on a final shape of our coverage trace I’ve run some tests and I wasn’t very happy with the results. Keeping the granularity on a function level was generating only few distinct values of coverage regardless of applied mutations. Current coverage is made with basic blocks resolution but that also resulted in very heavy performance hit. Let’s hope it will be worth it in the end.

With the coverage fixed it’s time to find a new way to mutate our samples. As you might remember our old mutation strategy had only one round. Mutations were applied perpetually to an initial corpus of files and resulting samples were fed to a program. With trace information discarded there was no feedback loop and promising changes that exposed completely new functionality but didn’t resulted in a crash were lost. Our new mutation strategy is going to fix that - it will be multi-stage with a feedback loop.

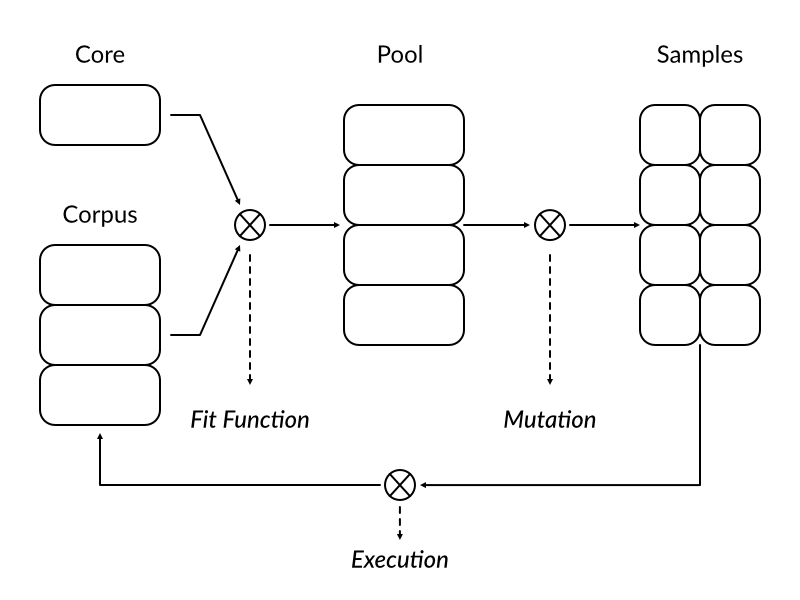

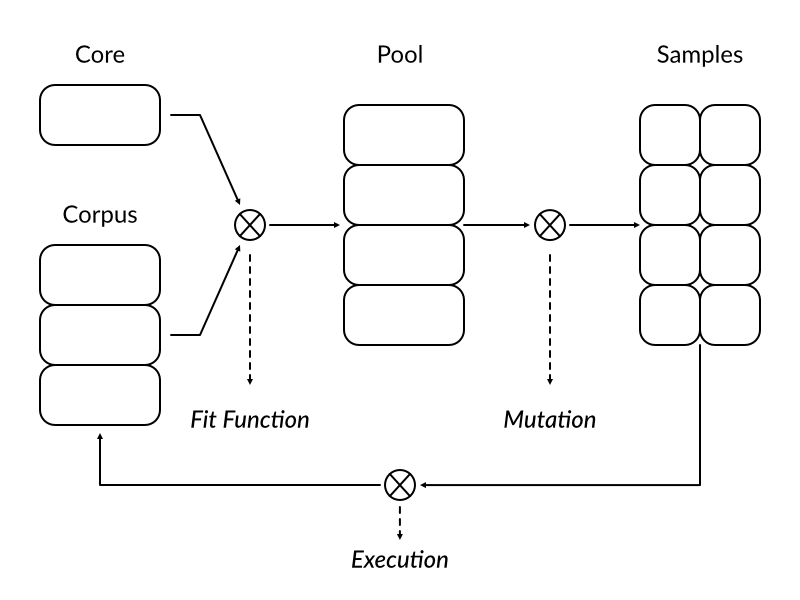

Before anyone asks - diagram was made using Affinity Designer. It’s like an Inkscape but works.

On the picture above we see a simplified diagram of our new mutation strategy. Typical round begins with fit function deciding which samples from core set and corpus are best suited to be promoted to a mutation pool. Chosen samples are then mutated forming a new body of samples to be fed to execution engine. After the target program finishes processing individual sample it is placed back in the corpus together with a trace information. When all mutated samples from a given round are processed a new round begins.

In Python the best way to accomplish the multi-stage goal is to implement our Mutator as an iterable object.

Such objects are typically used in language constructs like for element in collection. In this example collection is an iterable object and element is whatever it emits in every iteration.

If you want the class to be used as iterable you need to implement iteration protocol - in Python it consists of two methods - __iter__ and __next__. Former is responsible for initializing the iterator while the latter is called every time a new element is requested. I’ve implemented it as follows:

class Mutator:

def __init__(self, core):

# core set of samples

self.core = core

# Data format = > (array of bytearrays, coverage)

self.trace = set() # Currently observed blocks

self.corpus = [] # Corpus of executed samples

self.pool = [] # Mutation pool

self.samples = [] # Mutated samples

def __iter__(self):

# Initiate mutation round

self._fit_pool()

self._mutate_pool()

return self

def __next__(self):

if not self.samples:

self._fit_pool()

self._mutate_pool()

global stop_flag

if stop_flag:

raise StopIteration

else:

return self.samples.pop()

There are two things I would like to explain better. Our mutator is expected to run continuously but it is impractical to generate infinite number of samples. We also don’t want to trigger mutation every time a sample is requested. Our solution takes advantage of the fact that we have full control over __next__ - we mutate several samples in advance and when the current supply is exhausted we trigger a new mutation stage.

Given that our mutator executes infinite loop we also had to add a global stop_flag that is set by the SIGINT handler - simply hitting CTRL-C will stop the fuzzer. Otherwise, it will keep running forever.

Next task is to figure it out how are we going to mutate the samples. The code bellow shows the current implementation.

class Mutator:

[...]

def _mutate_pool(self):

# Create samples by mutating pool

while self.pool:

sample,_ = self.pool.pop()

for _ in range(10):

self.samples.append(Mutator.mutate_sample(sample))

The premise here is fairly simple - for every file in a mutation pool we create ten different samples by applying random mutations. Ten is of course very arbitrary number and there is no prior research on my part here. I’ve just picked it because it’s a nice round number, however I’m sure that someone somewhere wrote a PhD about optimal mutation strategies in genetic algorithms.

When it comes to how we are actually going to mutate the sample I’ve decided against revolutionary changes. Take a look at code bellow:

@staticmethod

def mutate_sample(sample):

_sample = sample[:]

methods = [

Mutator.bit_flip,

Mutator.byte_flip,

Mutator.magic_number,

Mutator.add_block,

Mutator.remove_block,

]

f = random.choice(methods)

idx = random.choice(range(0, len(_sample)))

f(idx, _sample)

return _sample

If it look familiar it is because, with small changes, I’ve copied it from the previous version of the fuzzer. There are some changes worth explaining. We no longer select a percentage of all bytes in a file for mutation. Such aggressive method was useful when we only had one round - with many rounds it would most likely render file unreadable by target program. In this version decision how many bits or bytes to mutate is randomized and left to the individual mutation technique.

You might have also noticed that a list of mutation method is now longer than we previously had. While bit_flip() and magic_number() remained unchanged and byte_flip() is a trivial variation of the bit_flip() the other two are bit more interesting.

@staticmethod

def add_block(index, _sample):

size = random.choice(SIZE)

_sample[index:index] = bytearray((random.getrandbits(8) for i in range(size)))

@staticmethod

def remove_block(index, _sample):

size = random.choice(SIZE)

_sample = _sample[:index] + _sample[index+size:]

The goal of a given function is expressed by its name but there is one thing worth exploring. If we ever decide to add dictionaries to our fuzzer this would be a good place to integrate it.

Backbone of every genetic algorithm is something called a fit function. Its task is to select the most promising candidates for the next stage of mutation. It usually performs this by first, applying some arbitrary score to all the samples and second, by promoting the samples with a preference of ones with the highest score.

Our fuzzer uses two-dimensional score calculated from the trace data obtained during execution. First dimension is the presence of previously unknown basic block. We want to promote samples that uncovered some new functionality in the program. Second dimension is just the number of executed basic blocks - we want to promote samples with highest code coverage.

Implementation is not very complicated, but some parts warrant a closer look.

def _fit_pool(self):

# fit function for our genetic algorithm

# Always copy initial corpus

print('### Fitting round\t\t')

for sample in self.core:

self.pool.append((sample, []))

print('Pool size: {:d} [core samples promoted]'.format(len(self.pool)))

# Select elements that uncovered new block

for sample, trace in self.corpus:

if trace - self.trace:

self.pool.append((sample, trace))

print('Pool size: {:d} [new traces promoted]'.format(len(self.pool)))

# Backfill to 100

if self.corpus and len(self.pool) < 100:

self.corpus.sort(reverse = True, key = lambda x: len(x[1]))

for _ in range(min(100-len(self.pool), len(self.corpus))):

# Exponential Distribution

v = random.random() * random.random() * len(self.corpus)

self.pool.append(self.corpus[int(v)])

self.corpus.pop(int(v))

print('Pool size: {:d} [backfill from corpus]'.format(len(self.pool)))

print('### End of round\t\t')

# Update trace info

for _, t in self.corpus:

self.trace |= t

# Drop rest of the corpus

self.corpus = []

We do the fitting in three distinct stages:

In the first stage we promote samples from the initial corpus. Those samples will always start pure and without any mutation. It’s some sort of control group. The reason for this step is my worry, that if we allow only samples with accumulated mutations we might drift away from the initial high coverage.

Next stage focuses on promoting all the samples that have managed to uncover previously unvisited code paths in the program. I’ve decided not to do any pre-selection here and instead to give a chance to all of those ones.

Last stage just fills the mutation pool to have at least one hundred samples. It’s possible that the previous round failed to produce enough samples that discovered new code paths. In such a situation we calculate how many samples we are missing and promote the required number of samples from the corpus using other criteria - we sort the corpus in descending order and pick samples using a probability function.

This probability function is actually worth explaining a bit more. If we just select a random element from the corpus it would be a uniform distribution and our ordering wouldn’t make much sense. However, if we multiply two random numbers in the range between 0 and 1 the product is more probable to be closer to 0 than to 1. That means that samples with higher coverage are more likely to be promoted to the next round.

In the end function performs some administrative tasks - collecting the trace information and deleting the rest of the corpus.

With the fit function implemented we have all the elements of coverage guided fuzzer. After testing I was happy to see that it is still capable of finding bugs in easy targets.

Goes without saying that it still has many drawbacks - speed is just atrocious and the mutation strategy is most likely very far from optimal. It has one advantage - it is simple and the code should be readable by anyone just starting their fuzzing adventure. After that brief introduction you should be able to read AFL whitepaper and understand it.

Quite frankly I’m not sure what else I should add here and should there be any subsequent parts. Don’t get me wrong - there are tons of improvements we can add. We can rewrite it to some decent language, implement better instrumentation or improve our mutator. If you have any good ideas please do not hesitate to reach out to me - my twitter address is just below. There is nothing better than getting a message from a happy reader.